The driving simulator – a virtual truck of the future

The truck drives out after making a right-hand turn and accelerates along the straight stretch of road ahead. Its engine speed increases and the trees flash past the cab windows. The vibrations from the uneven road surface can be clearly felt in the body. Nothing surprising there – except that everything that is heard, felt and seen is simulated by a computer!

“The basic idea behind the simulator is to create a feeling of reality. It should sound and feel exactly as it does when you drive a truck on a normal road,” says Kristoffer Tagesson, an industrial PhD student at Volvo Trucks.

This driving simulator, which is owned by the Swedish research institute, VTI (Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute), is regarded as one of the most advanced in the world. The research that is being conducted is designed to develop safety for current and future vehicles. Volvo Trucks is one of a number of partners within the transport industry that are conducting research in the simulator with a view to developing the world’s safest trucks.

Collision tests are excellent – they can be breath-taking to watch and they are also one of the most effective ways of testing truck capacity in a collision, but traffic safety is so much more than just smashed windows and windscreens and crumpled sheet metal.

“In a collision test, we can see what happens at the actual moment of impact – but what happens before that? How do we know that the active safety systems don’t distract the driver in a critical situation but instead actually help him or her? These are the types of question that are being investigated here,” explains Kristoffer Tagesson.

The basic idea behind the simulator is to create a feeling of reality. It should sound and feel exactly as it does when you drive a truck on a normal road.

He is sitting in the operator’s room, where a number of computers document the way the test drivers’ drives, watches and positions him/herself on the road. Enormous amounts of information are collected. One of the main advantages of this driving simulator, which is a relatively new kind of test technology, is that it is now possible to include the driver at an early stage in the development of new products.

“It has traditionally been necessary to build everything first – roads, vehicles and safety systems – before tests could be conducted to see if it works in practice. However, it is now possible to do this in parallel,” explains Kristoffer Tagesson.

In other words, the driving simulator makes it possible to test new vehicles in future driving environments and to do it now. Peter Nilsson, another industrial PhD student at Volvo Trucks, is involved in precisely this kind of project.

“The work that is being done on vehicle and infrastructure development is based on a long-term perspective. With this simulator, which is able to visualise basically any road environment, we can optimise these developments together,” he says.

Peter Nilsson’s project is called Safe Corridors and it is investigating ways of finding safe corridors for long vehicle combinations, between 27 and 34 metres.

“By 2020-2030, I am convinced that we shall have these long vehicle combinations on the road, as they are such an environmentally efficient alternative. By then, however, we need to find a way of facilitating driving for the driver, as knowing the exact position of the trailer is a real challenge,” explains Peter Nilsson.

So, using a sophisticated driver system, it will be possible in the future for the actual vehicle to calculate a safe position for itself on the road, using information from the surrounding road, signs and other vehicles.

“The idea is that this autonomous system will intervene and take control from the driver if it sees that the vehicle is outside the safe corridor. Our challenge now is to find out how this transfer should be made, as it’s important that it feels natural for the driver.”

A test was recently conducted in the driving simulator in which 20 drivers tested two different autonomous driving systems. They were then asked subjectively to assess which of the systems was better. However, as an experienced driver knows better than anyone else how a vehicle should behave on the road, Peter Nilsson also allowed the test drivers to drive the long vehicle combination themselves.

“We were then able to record and objectively analyse how these experienced drivers drove a 30-metre vehicle on challenging roads. In the future, we shall be able to use this as part of the basic documentation when we develop safe corridors and design this autonomous system.”

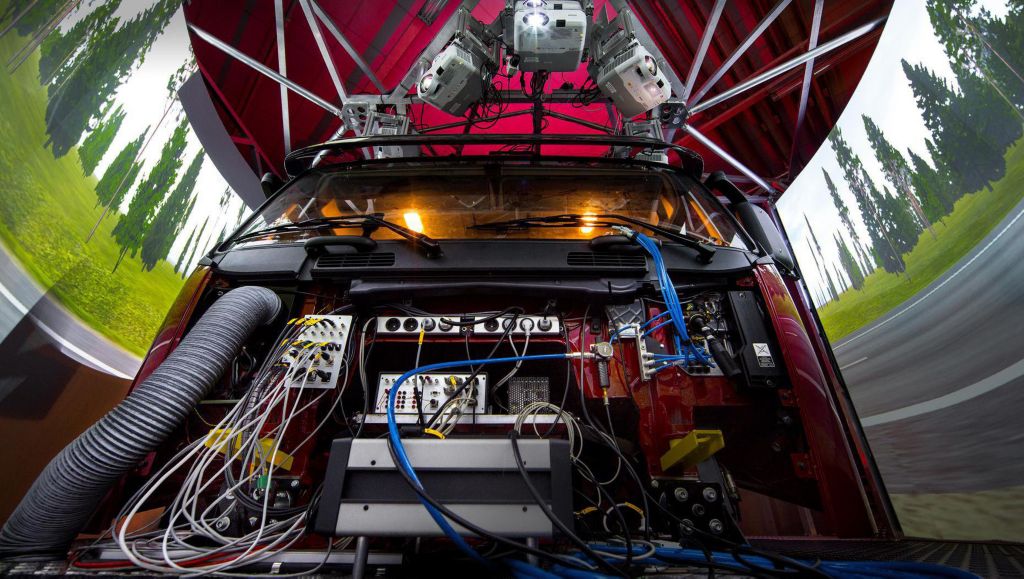

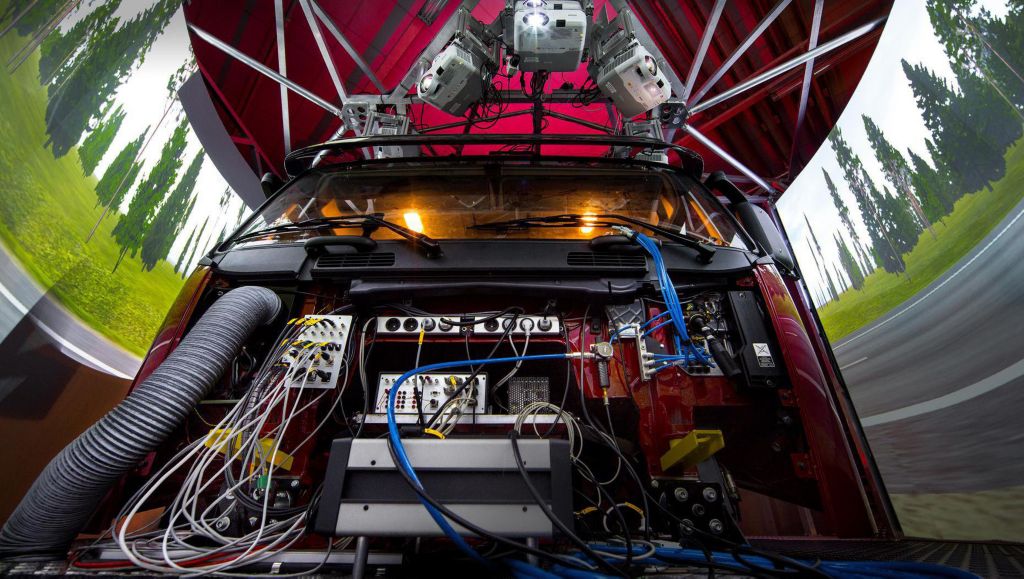

The tests that are being conducted are made possible by the sophisticated technology in the simulator. The simulator is located on two intersecting rails, which make it possible to create the experience of driving forwards and backwards, as well as turning. The truck cab is also able to move vertically. This creates a realistic driving experience, when it comes to both steering functions and chassis vibrations.

By generating this detailed picture of the way the driver actually behaves, we can identify potential for improving our own safety system.

The cab is also equipped with ten cameras, all of which document the driver’s behaviour. Five cameras are visibly located in the windscreen in front of the driver. They use infrared light to record and register all the driver’s eye movements. This enables researchers to see exactly where, when and how often the driver looks at the road and looks down at his/her phone and GPS (satnav system), for example.

Five of the cameras are well concealed inside the cab, so that the driver does not think about them. They document other typical things the driver’s do – everything from handling the steering wheel to accelerator and pedal movements using his/her feet is recorded.

Another exciting project which is currently being run by Volvo Trucks is aiming to find a mathematical description of driver behaviour – a so-called driver model. This will then be used to evaluate the active safety systems.

Systems, already on the market, such as Collision Warning with Emergency Brake have been tested in the simulator. One by one, 46 drivers sat in the simulator without knowing what was going to happen while they were driving. After 30 minutes driving, a critical situation was simulated and the safety system was activated.

“This enables us to see how quickly the driver reacts to the warning, how he or she manages with and without the system and whether there is any difference in the reactions of the people who already have some experience of the system. By generating this detailed picture of the way the driver actually behaves, we can identify potential for improving our own safety system,” says Gustav Markkula, an industrial PhD student who is responsible for this project.

“As a researcher, it’s important to be given the chance to meet our drivers and hear what they actually think of our products and solutions. I think this is the key to success.”